What is code coverage?

Code coverage is a white-box testing technique used in software testing as a critical metric to measure the degree to which the source code of a program is executed when a particular test suite runs. The idea is that a higher level of code coverage means that more code has been executed during testing, suggesting a lower chance of undetected bugs making it through compared to a program with low code coverage.

A common misconception among developers and managers is that code coverage refers to the “percentage of code that has been properly tested,” but this is often not the case. This subtle distinction is the difference between what they think they are measuring and what exactly is being measured. Misusing the term “code coverage” in this manner may lead to a false sense of security.

Code Coverage (%) = (Number of Covered Code Units / Total Number of Code Units) × 100

Nowadays, companies may choose to specify a minimum percentage of code coverage threshold, commonly around 80% across an entire application. At first, this sounds like a great idea, as it’s a common saying that the more code coverage you have, the better your code is. But in practice, this might make teams unable to work effectively.

Still, there is a constant debate in the software industry about its importance and validity, with some engineers arguing that it should not be an important metric because bad code can still be tested and will end up giving good coverage, but it will fail real-world scenarios.

Code vs. test coverage: a brief comparison example

Before we proceed, let’s quickly understand how code coverage differs from test coverage. These two terms get thrown around a lot and can get mixed up, since they are often used incorrectly.

The code below is a function for discounted prices for a shop where members get 20% off and non-members get 10% off.

def get_discounted_price(price, is_member):

if is_member:

discount = 0.2 # 20% discount for members

else:

discount = 0.1 # 10% discount for non-members

discounted_price = price - (price * discount)

return discounted_price

Here’s a test case for members alone:

class SimpleTest(unittest.TestCase):

def test_add1(self):

# Test case 1: Member with price 100

result = get_discounted_price(100, True)

assert result == 80.0

# Test case 2: Non-member with price 100

# result = get_discounted_price(100, False)

# assert result == 90.0With that, the code coverage will be 83%, because the test only executes five out of the six lines of code. Ideally, you might want 100%, as that shows you have tested all possible scenarios of the code.

On the other hand, test coverage measures the extent to which the test suite covers the requirements for the software. For example, if our code functions had the requirements to calculate the discounted price for members, non-members, negative prices, and zero prices, then our test coverage would be 25%. That is because in this test, we only handled one out of the four requirements.

Why do we need code coverage?

Here are some brief examples of why code coverage is needed today.

Code coverage can serve as an acceptance criterion, as it provides a quantifiable metric to evaluate the quality of work from subcontractors

Outsourcing projects to subcontractors

Code coverage can serve as an acceptance criterion, as it provides a quantifiable metric to evaluate the quality of work from subcontractors. This can be done by setting a threshold as part of the contract to ensure that all code is adequately tested.

Adhering to industry standards

Some industries with regulatory compliance, like aerospace (DO-17BC) and healthcare (IEC 62304), are actually mandated to have high code coverage to maintain safety and reliability. Code coverage reports can also serve as evidence that can be used to pass audits and achieve certifications.

Standardizing quality

Enforcing a coverage standard and a test-writing culture will ensure consistency across all projects and prevent developers from skipping it, maybe due to time constraints, thus making the software more maintainable and dependable in the long run.

Types of code coverage

Statement coverage (or line coverage)

This is the simplest metric used to design white-box test cases, which aims to measure the percentage of executable statements (lines of code) in an application’s source code that have been executed at least once during testing. It answers the common question, “Has this line of code been run?”

It works by tracking each executable line and marking it as “covered” once the execution passes that line. You should also note that comments, declarations, and blank lines are not counted.

This can be calculated using the formula: (Total statement executed / Total number of executable statements in the program) x 100

Consider this code example:

def calculate_discount(price, customer_type):

# This function calculates a discount based on price and customer type

if price > 100: # Line 1 - Decision point

base_discount = 0.1 # Line 2 - Executed if price > 100

else:

base_discount = 0.05 # Line 3 - Executed if price <= 100

if customer_type == "premium": # Line 4 - Another decision point

additional_discount = 0.05 # Line 5 - Executed for premium customers

else:

additional_discount = 0 # Line 6 - Executed for regular customers

total_discount = base_discount + additional_discount # Line 7 - Always executed

return price * (1 - total_discount) # Line 8 - Always executed

Statement coverage test cases

And let’s look at sample test cases for it:

def test_statement_coverage():

# Test Case 1: High price, premium customer

# This will execute: Lines 1(True), 2, 4(True), 5, 7, 8

result1 = calculate_discount(150, "premium")

assert result1 == 127.5 # 150 * (1 - 0.15) = 127.5

# Test Case 2: Low price, regular customer

# This will execute: Lines 1(False), 3, 4(False), 6, 7, 8

result2 = calculate_discount(80, "regular")

assert result2 == 76.0 # 80 * (1 - 0.05) = 76.0

Coverage analysis:

Line 1: ✓ Executed (both True and False paths tested)

Line 2: ✓ Executed (Test Case 1)

Line 3: ✓ Executed (Test Case 2)

Line 4: ✓ Executed (both True and False paths tested)

Line 5: ✓ Executed (Test Case 1)

Line 6: ✓ Executed (Test Case 2)

Line 7: ✓ Executed (both test cases)

Line 8: ✓ Executed (both test cases)

This will result in Statement Coverage: 8/8 lines = 100%. Now, why is that, you may ask? Well, you need to understand that even though we only have two test cases, we’ve managed to execute every single line of code once.

Advantages of statement coverage

- It’s a good starting point for teams and projects who are adopting code coverage.

- It’s very easy to implement, as most code coverage tools already provide it out of the box.

- It’s widely supported in multiple programming languages and testing frameworks.

Disadvantages of statement coverage

- It will miss edge cases and may not catch bugs in conditional expressions.

- 100% statement coverage doesn’t translate to bug-free software.

- Statement coverage measures reach, not quality.

Branch coverage

This measures whether each possible branch from every decision point has been executed. The focus is on the outcomes of conditionals (if/else, switch cases, etc.) and ensuring that both true and false paths are tested. Branch coverage looks at decision points in code and tracks to see whether both outcomes have been tested.

Code example:

def process_order(quantity, stock, user_type):

"""

Process an order with multiple validation steps and user type handling

Args:

quantity: Number of items to order

stock: Available stock

user_type: Type of user ("vip" or "regular")

Returns:

String message about order status

"""

# Decision Point A: Validate quantity

if quantity <= 0: # Branch A

return "Invalid quantity" # Branch A-True

# Decision Point B: Check stock availability

if quantity > stock: # Branch B

return "Insufficient stock" # Branch B-True

# Decision Point C: Determine discount based on user type

if user_type == "vip": # Branch C

discount = 0.2 # Branch C-True

else:

discount = 0.1 # Branch C-False

# Calculate final price (assuming $10 per item)

total = quantity * 10 * (1 - discount)

return f"Order processed: ${total}"

Decision points analysis:

- Branch A: quantity <= 0 can be True (invalid) or False (valid)

- Branch B: quantity > stock can be True (insufficient) or False (sufficient)

- Branch C: user_type == “vip” can be True (VIP) or False (regular)

Test cases of branch coverage

def test_branch_coverage():

# Test Case 1: Branch A-True (Invalid quantity)

# Path: A-True → return "Invalid quantity"

result1 = process_order(-1, 10, "regular")

assert result1 == "Invalid quantity"

print("✓ Branch A-True covered: Invalid quantity handled")

# Test Case 2: Branch A-False, Branch B-True (Insufficient stock)

# Path: A-False → B-True → return 'Insufficient stock'

result2 = process_order(15, 10, "regular")

assert result2 == "Insufficient stock"

print("✓ Branch A-False, B-True covered: Stock validation handled")

# Test Case 3: Branch A-False, Branch B-False, Branch C-True (VIP customer)

# Path: A-False → B-False → C-True → Order processed with VIP discount

result3 = process_order(5, 10, "vip")

assert result3 == "Order processed: $40.0" # 5 * 10 * (1 - 0.2) = 40

print("✓ Branch A-False, B-False, C-True covered: VIP discount applied")

# Test Case 4: Branch A-False, Branch B-False, Branch C-False (Regular customer)

# Path: A-False → B-False → C-False → Order processed with regular discount

result4 = process_order(5, 10, "regular")

assert result4 == "Order processed: $45.0" # 5 * 10 * (1 - 0.1) = 45

print("✓ Branch A-False, B-False, C-False covered: Regular discount applied")

Analysis of branch coverage:

- Branch A-True: ✓ Covered (Test Case 1)

- Branch A-False: ✓ Covered (Test Cases 2, 3, 4)

- Branch B-True: ✓ Covered (Test Case 2)

- Branch B-False: ✓ Covered (Test Cases 3, 4)

- Branch C-True: ✓ Covered (Test Case 3)

- Branch C-False: ✓ Covered (Test Case 4)

Branch coverage: 6/6 branches = 100%

Why is this more thorough than statement coverage?

Unlike statement coverage, branch coverage tries to ensure that every possible decision outcome is tested. By following this approach, more logical errors are caught, because it forces you to test for both success and failure scenarios.

However, it might still pose challenges, like not being able to catch all issues in deeply nested conditional logic. Also, it’s harder to hit 100% in complex codebases, as it may miss boolean expressions.

When there are complex conditions with AND, OR, and NOT operators, condition coverage ensures that each boolean expression is tested in both states

Condition coverage

This measures whether each boolean sub-expression in conditional statements has been evaluated to both true and false at least once. When there are complex conditions with AND, OR, and NOT operators, condition coverage ensures that each boolean expression is tested in both states. This is very crucial for catching bugs in complex logical conditions.

Here is some code, and then we’ll test it in the next section:

function canAccess(user) {

// Complex condition with multiple boolean expressions

// Condition A: user.isActive

// Condition B: user.role === 'admin'

// Condition C: user.permissions.includes('read')

if (

user.isActive &&

(user.role === 'admin' || user.permissions.includes('read'))

) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

Condition coverage test cases

describe('Condition Coverage Tests', () => {

// Test 1: A=true, B=true, C=true

test('active admin with read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: true,

role: 'admin',

permissions: ['read', 'write']

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(true);

});

// Test 2: A=true, B=true, C=false

test('active admin without read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: true,

role: 'admin',

permissions: ['write']

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(true);

});

// Test 3: A=true, B=false, C=true

test('active non-admin with read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: true,

role: 'user',

permissions: ['read']

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(true);

});

// Test 4: A=true, B=false, C=false

test('active non-admin without read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: true,

role: 'user',

permissions: ['write']

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(false);

});

// Test 5: A=false, B=true, C=true

test('inactive admin with read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: false,

role: 'admin',

permissions: ['read']

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(false);

});

// Test 6: A=false, B=false, C=false

test('inactive non-admin without read permission', () => {

const user = {

isActive: false,

role: 'user',

permissions: []

};

expect(canAccess(user)).toBe(false);

});

});

Condition coverage analysis:

A (user.isActive): tested as true and false ✓

B (user.role === ‘admin’): tested as true and false ✓

C (user.permissions.includes(‘read’)): tested as true and false ✓

Condition coverage: 3/3 conditions tested in both states = 100%

Advantages of condition coverage

- Perfect for granular testing and leads to a better understanding of the code logic.

Disadvantages of condition coverage

- Requires writing more test cases than branch coverage.

- Might create maintenance overhead, as more tests will need to be written when code changes.

Path coverage

This measures whether each execution path through the program has been tested. It’s the most comprehensive form of coverage testing.

It works by considering all possible routes, including different combinations of conditional branches, loops, and function calls. When it comes to programs with loops, the possible paths can be infinite, thus making complete path coverage impractical.

Code example:

def process_order(order_value, customer_type, has_coupon):

"""Process an order with multiple decision points"""

total = order_value

# Decision Point 1: Order value check

if order_value > 100:

shipping_cost = 0 # Free shipping

else:

shipping_cost = 10

# Decision Point 2: Customer type check

if customer_type == "premium":

discount = 0.15

else:

discount = 0.05

# Decision Point 3: Coupon check

if has_coupon:

discount += 0.10

total = (order_value - (order_value * discount)) + shipping_cost

return total

Path coverage test cases

# Path 1: order_value > 100, premium customer, has coupon

def test_path_1():

result = process_order(150, "premium", True)

expected = (150 - (150 * 0.25)) + 0 # 112.5

assert result == expected

# Path 2: order_value > 100, premium customer, no coupon

def test_path_2():

result = process_order(150, "premium", False)

expected = (150 - (150 * 0.15)) + 0 # 127.5

assert result == expected

# Path 3: order_value > 100, regular customer, has coupon

def test_path_3():

result = process_order(150, "regular", True)

expected = (150 - (150 * 0.15)) + 0 # 127.5

assert result == expected

# Path 4: order_value > 100, regular customer, no coupon

def test_path_4():

result = process_order(150, "regular", False)

expected = (150 - (150 * 0.05)) + 0 # 142.5

assert result == expected

# Path 5: order_value <= 100, premium customer, has coupon

def test_path_5():

result = process_order(80, "premium", True)

expected = (80 - (80 * 0.25)) + 10 # 70

assert result == expected

# Path 6: order_value <= 100, premium customer, no coupon

def test_path_6():

result = process_order(80, "premium", False)

expected = (80 - (80 * 0.15)) + 10 # 78

assert result == expected

# Path 7: order_value <= 100, regular customer, has coupon

def test_path_7():

result = process_order(80, "regular", True)

expected = (80 - (80 * 0.15)) + 10 # 78

assert result == expected

# Path 8: order_value <= 100, regular customer, no coupon

def test_path_8():

result = process_order(80, "regular", False)

expected = (80 - (80 * 0.05)) + 10 # 86

assert result == expected

Path coverage: 100% (all 8 possible paths tested)

3 decision points with 2 outcomes each = 23 = 8 paths

Advantages of path coverage

- It’s excellent at finding interaction bugs which only occur with specific combinations of decisions.

Disadvantages of path coverage

- It can get very complex when the number of paths increases exponentially with decision points.

- It can slow down development and test cycles.

Function coverage

This measures whether functions or methods have been called during a test. It works by tracking each function definition in a codebase and marking it as covered when the test suite calls that function at least once. It’s particularly useful in identifying unused and dead code.

Example code:

public class MathUtilities

{

// Function 1

public int Add(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

// Function 2

public int Subtract(int a, int b)

{

return a - b;

}

// Function 3

public int Multiply(int a, int b)

{

return a * b;

}

// Function 4

public double Divide(int a, int b)

{

if (b == 0)

throw new DivideByZeroException("Cannot divide by zero");

return (double)a / b;

}

// Function 5 - Helper

private bool IsEven(int number)

{

return number % 2 == 0;

}

// Function 6

public string GetNumberType(int number)

{

if (IsEven(number))

return "Even";

return "Odd";

}

// Function 7 - Not covered

public int Power(int baseNumber, int exponent)

{

int result = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < exponent; i++)

{

result *= baseNumber;

}

return result;

}

}

Function coverage test cases

And here’s testing for the code above:

[TestClass]

public class MathUtilitiesTests

{

private MathUtilities _mathUtils = new MathUtilities();

[TestMethod]

public void TestAdd()

{

Assert.AreEqual(5, _mathUtils.Add(2, 3));

// Function 1 covered ✓

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestSubtract()

{

Assert.AreEqual(1, _mathUtils.Subtract(3, 2));

// Function 2 covered ✓

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestMultiply()

{

Assert.AreEqual(6, _mathUtils.Multiply(2, 3));

// Function 3 covered ✓

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestDivide()

{

Assert.AreEqual(2.5, _mathUtils.Divide(5, 2));

// Function 4 covered ✓

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestGetNumberType()

{

Assert.AreEqual("Even", _mathUtils.GetNumberType(4));

Assert.AreEqual("Odd", _mathUtils.GetNumberType(5));

// Function 6 covered ✓

// Function 5 (IsEven) indirectly covered ✓

}

// Function 7 (Power) is NOT covered in tests

}

Function coverage analysis:

Total functions: 7

Covered: 6 (Add, Subtract, Multiply, Divide, IsEven, GetNumberType)

Not covered: 1 (Power)

Function coverage: 6/7 = 85.7%

Set realistic code coverage goals and aim for practical coverage targets rather than an unrealistic 100%

Best practices for code coverage

Here are some best practices to use when getting started with code coverage:

- Set realistic code coverage goals and aim for practical coverage targets rather than an unrealistic 100%.

- Combine multiple coverage metrics to achieve more comprehensive insight into how effective your tests are.

- Integrate coverage into CI/CD pipelines.

- Regularly review and refine test suites.

- Extend coverage beyond unit tests.

- Complement with test coverage strategies.

Comprehensive code coverage with Tricentis Sealights

Over the years, it’s been discovered that most engineering teams lack robust code coverage beyond writing unit tests. This leaves other types of tests—such as end-to-end (E2E), regression, system, integration, and API tests—unmeasured, resulting in an inconclusive and inaccurate code coverage result.

In an attempt to solve this, Tricentis acquired SeaLights in July 2024, which is an AI-powered software quality intelligence platform that dynamically analyzes your code and identifies the code coverage for every test type, whether they are manually run or automated.

How SeaLights enhances coverage visibility

With SeaLights Test Gap Analysis (TGA), it goes a step further to handle Code Changes Coverage. Unlike other standard enterprise tools, SeaLights uses ML agents to map code changes to tests (spanning all test types) and expose untested code changes across all testing stages and types, making sure you don’t push modified or newly added code to production without testing it.

Additionally, since Agile teams are fast-paced, they often have tight testing deadlines and thousands of requirements that must be met with each release. The ability to identify which tests are related to code changes, without needing to run all tests in a test suite every time a new release is due, can quickly reduce bottlenecks and strain on testers.

SeaLights also solves this, as it leverages the Test Impact Analysis (a Smart Test Execution Engine) feature to identify any untested changes made, automatically selecting and executing only those related to the code changes and allowing you to skip the irrelevant ones for each build and release. This single-handedly cuts testing cycle times by 50% to 90%, thus significantly reducing the number of unnecessary failed tests.

Real-time quality intelligence

“The additional capabilities of SeaLights further extend the dominance of our comprehensive quality intelligence solutions to a wide array of applications and environments.” – Kevin Thompson, Chief Executive Officer, Tricentis

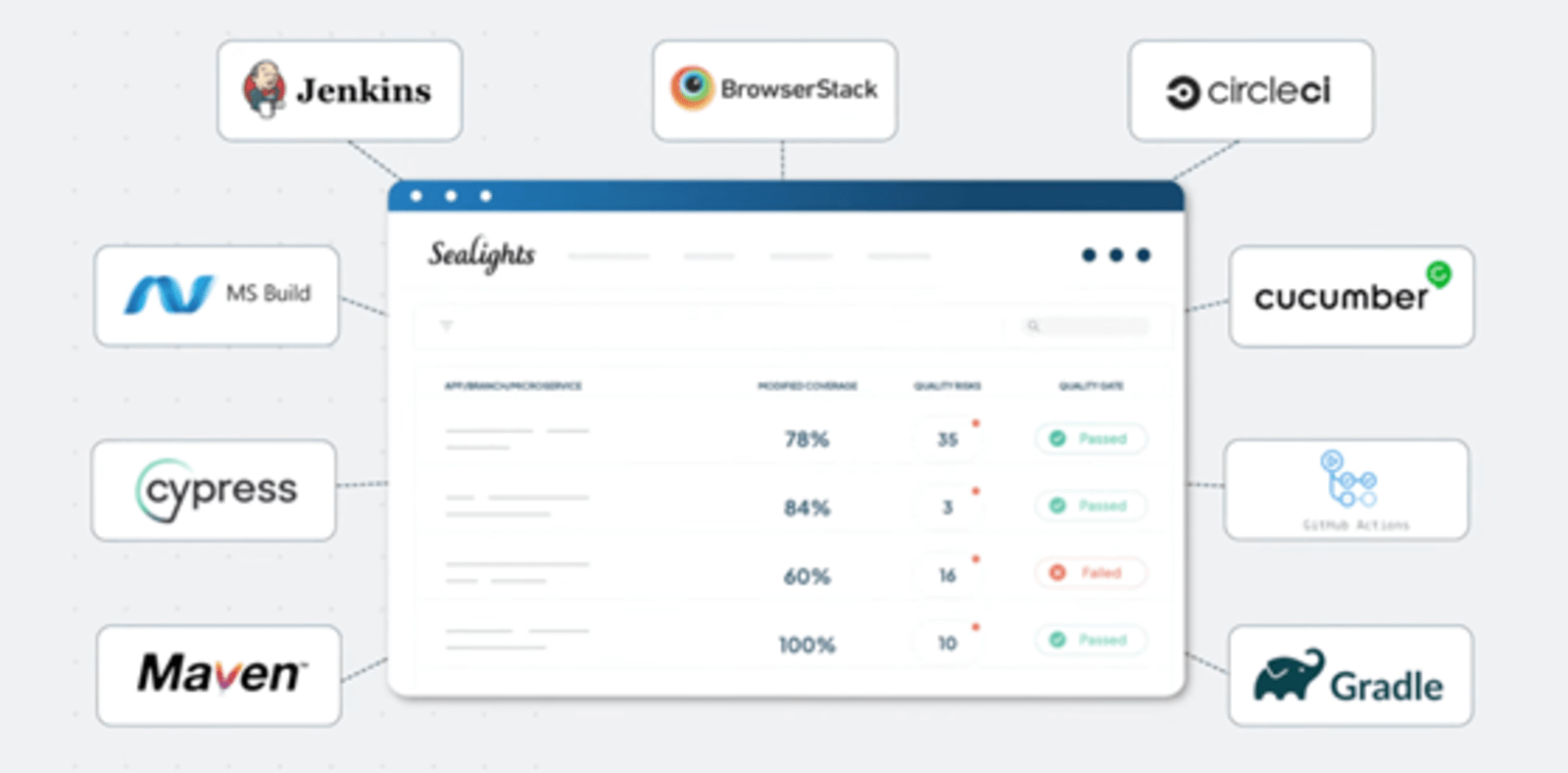

Furthermore, it integrates with every build, CI, and testing framework to provide real-time insights, so testers can quickly identify critical changes and their impact on the project.

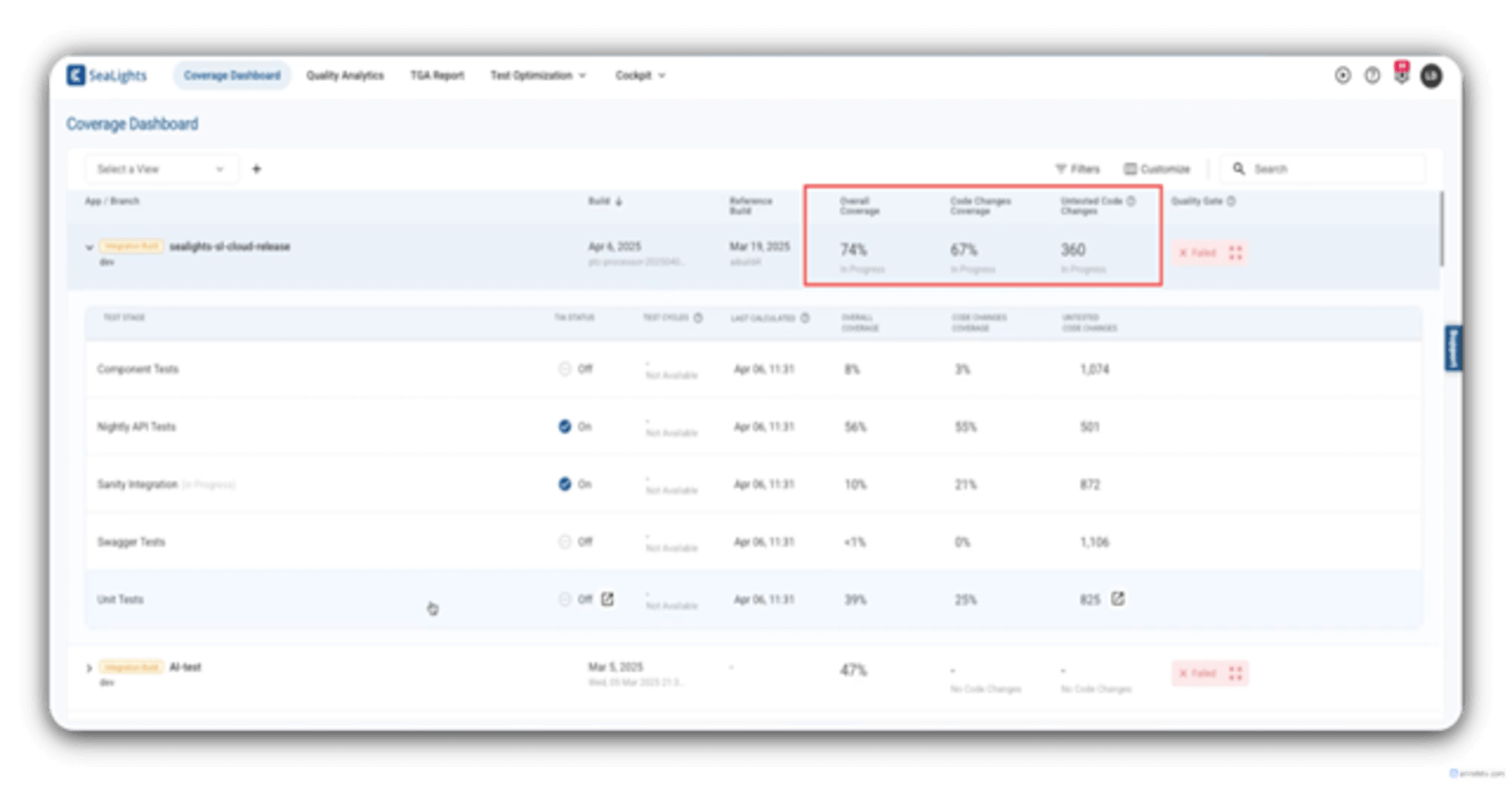

After integration, in the SeaLights main Coverage Dashboard, you can see a sample breakdown of the coverage under some quality metrics first for each test type, and then an Overall Coverage percentage, Code Changes Coverage percentage, and an Untested Code Changes report for an entire build, all at once and in one place.

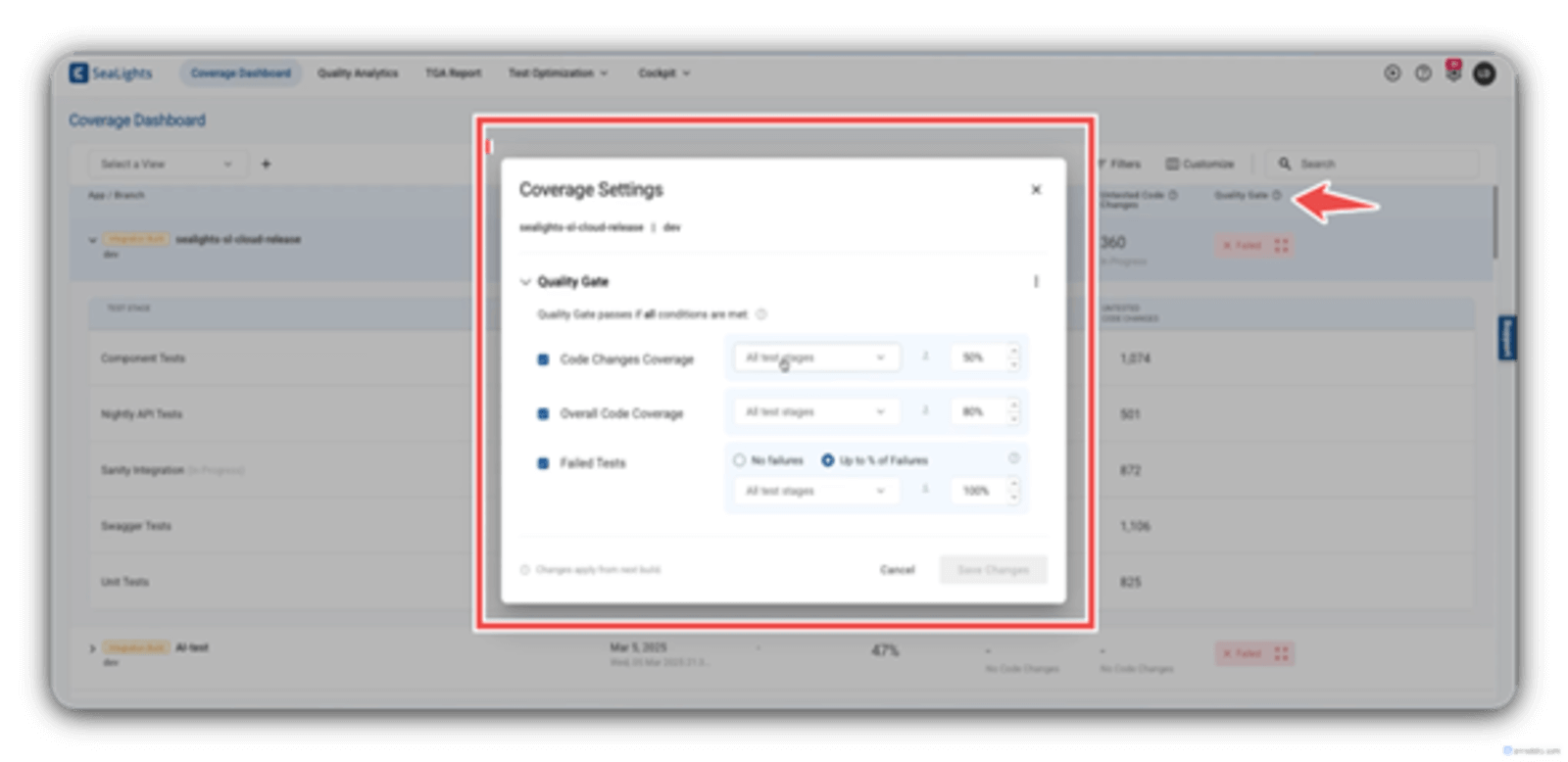

That is not all, as you can also set your company’s specific quality standard using the Quality Gate coverage settings (which are very much customizable).

Integrations and benefits

For a more visual code coverage representation, you can integrate SeaLights with tools that make use of user stories and epics. By having this detailed insight into overall code coverage, SeaLights aims to empower teams (e.g., SAP teams) to make faster releases while achieving zero production defects/errors and maintaining high software quality. Troubleshooting is now much easier and faster, as the focus is only on relevant tests.

It’s also designed to integrate with your preferred CI/CD tools such as Jenkins, Azure DevOps, GitLab, and CircleCI. Currently, it supports languages like GoLang and Python and testing frameworks including Protractor, Jest, Robot Framework, AVA, Karma, and Mocha. You also have the option to use its API if needed.

Still curious to learn more? Watch this webinar, or better yet, you can sign up for a personalized 1:1 demo from one of our experts at Tricentis.

This post was written by Wisdom Ekpotu. Wisdom is a software and technical writer based in Nigeria. Wisdom is passionate about web/mobile technologies, open-source software, and building communities. He also helps companies improve the quality of their technical documentation.